Who would have thought that our brains are better equipped to process cognitive tasks if we are exposed to light several hours beforehand? Researchers in Inserm Unit 846 “Stem Cells and Brain” and the Cyclotron Research Centre at the University of Liege (Belgium) have recently proven that this ‘delayed effect’ is due to a sort of light memory (or photic memory). The results of this work are published in the PNAS journal.

It has long been known that light exerts powerful effects on the brain and on our well-being. Light is not only required for vision but is also essential for a wide range of “non-visual” functions including synchronization of our biological clock to the 24h day-night cycle. Light also conveys a powerful stimulating signal for human alertness and cognition and has been routinely employed to improve performance, counter the negative impact of sleepiness or “winter blues”.

The mechanisms underlying these positive effects of light still remain largely unknown.

However, within the last decade or so, researchers have discovered a new type of light sensitive cell (photoreceptor) in the eye called melanopsin. This novel photoreceptor has been shown to be an essential component for relaying light information to a set of so-called non-visual centers in the brain. In the absence of this photoreceptor, animal research showed that non-visual functions are disrupted, the biological clock becomes deregulated and ‘free-runs” independent from the 24 day-night cycle and the stimulatory influence of light is impaired.

The melanopsin photopigment is unusual in many aspects and differs from our rods and cones since it shows invertebrate-like properties and is maximally sensitive to blue light. In humans, it has not been possible to apply genetic tools to selectively isolate the precise role of this new photoreception system and consequently the role of melanopsin in human cognition and alertness has not been established.

However, researchers from the Cyclotron Research Centre of the University of Liège (Belgium) and of the Department of Chronobiology of the INSERM Stem Cell and Brain Research Institute (Bron, France) have just provided evidence demonstrating the involvement of melanopsin in the impact of light on cognitive brain function.

By exploiting the specific invertebrate-like responses of melanopsin combined with state-of-the-art functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) recording strategies, they were able to show that impact of light on brain areas recruited to perform an ongoing cognitive task depended on the specific color of previous light exposures.

Prior exposure 1-hr earlier to an orange light enhanced the subsequent impact of the test light, while prior exposure to blue light had the reverse outcome.

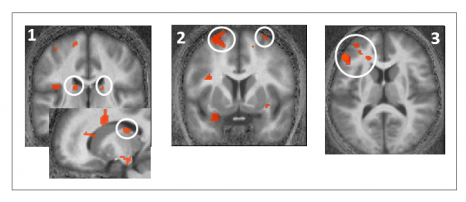

FIGURE: 16 young and health participants performed an auditory cognitive task while exposed to a test light. Brain areas in orange responded more to the test light if participants had been exposed to orange light 70 minutes earlier. 1. Thalamus; 2. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; 3. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.© Inserm/ Howard Cooper

These areas are important in the regulation of alertness and complex cognitive processes.

The phenomenon of prior light effects on a subsequent response to light is typical of melanopsin as well as certain photopigments of invertebrate and plant, and has been referred to as a “photic memory”.

“Humans may therefore have an invertebrate or plant-like machinery within the eyes that participates to regulate cognition. It may also explain what human chronobiologists have described as “previous light history effects”, a form of long term adaptation to previous lighting conditions,” explains Howard Cooper.

These findings emphasize the importance of light for human cognitive brain functions and constitute compelling evidence in favor of a cognitive role for melanopsin. More generally, the continuous change of light throughout the day also changes us. Ultimately, these findings argue for the use and design of lighting systems to optimize cognitive performance.